They say some funny things about Kersal Moor—and when I say “funny”, what I really mean is “odd”. If they ever made me laugh, they don’t any more.

There was a time when the moors ran all the way to the river, but that was long ago. These days, all that remains is a wild scrap of land by St Paul’s Church. On that sad little heath, footpaths cross the sandy hills, which are dotted with gorse and Scotch broom.

Everyone in a two mile radius knows that the moors were haunted once. Fewer know that they still are. They think the ghosts must have vanished by now, fading away as the moors got smaller. The truth is, they’re still around.

This is the story of how I met them.

When I was young, Grandpa had an awful-smelling dog called Din-Dins, which he used to walk down Moor Lane. From time to time I’d tag along. Mostly to listen to his stories but also to watch him smoke. Everyone smoked back then, but Grandpa rolled his own which wasn’t as common. He used to pinch the tobacco in a Rizla and lick the edge to seal it. Sometimes he let me do it for him, but I was sworn to secrecy on that point. I used to like it when a speck of tobacco stuck to my tongue because it gave my mouth a dangerous little buzz of nicotine.

One day, just by St Paul’s, Din-Dins stopped and gazed across the moor. He shook himself and whimpered.

“Does he want to come off his lead?” I wondered.

Grandpa shook his head.

“Not here,” he said. “That’s not yearning, lad. It’s fear.”

“What of?”

“Ghosts. Moor’s full of ’em.”

I looked at him in alarm.

“Don’t be daft,” I begged.

“I’m not. Have you finished that cigarette?”

“What? Oh.”

I licked the paper, pressed it down and handed it over. He lit the end and grunted with satisfaction.

“There’s a special time of year coming up,” he told me—resuming his story through a cloud of smoke—“called the winter solstice. Longest night of the year. When it falls on a new moon, it’s the darkest night there is. The two worlds are very close then.”

“Two worlds?”

“One of the living,” he clarified, “and one of the dead.”

He turned to the dreary heath that lay beside the road.

“If you come to Kersal Moor,” he added, “on that one special night, you can see the ghosts with your own two eyes. They call you to join ’em with a song. ‘O, unless you are a vicar / Hell will have your soul for sure / The Devil’s quick but we were quicker / Now we hide on Kersal Moor.’”

I shuddered.

“I don’t think I’d like that,” I said.

He seemed surprised.

“Really? Well you don’t go to join ’em straight away,” he explained. “It’s like a deal you make for later. When the sun rises, you go home and live your life as normal. You just don’t have to worry about hell any more. Instead, when you die, you join ’em on the moor instead of taking your chances with—you know—up or down.”

“When does it happen?”

“Which bit?”

I tried to remember the rules.

“A new moon on the longest night,” I recalled.

He shrugged and smoked his cigarette.

“God knows,” he said at last. “It happened in 1957, I know that much. Come on, Din-Dins!”

He gave the lead a little tug and we continued down Moor Lane.

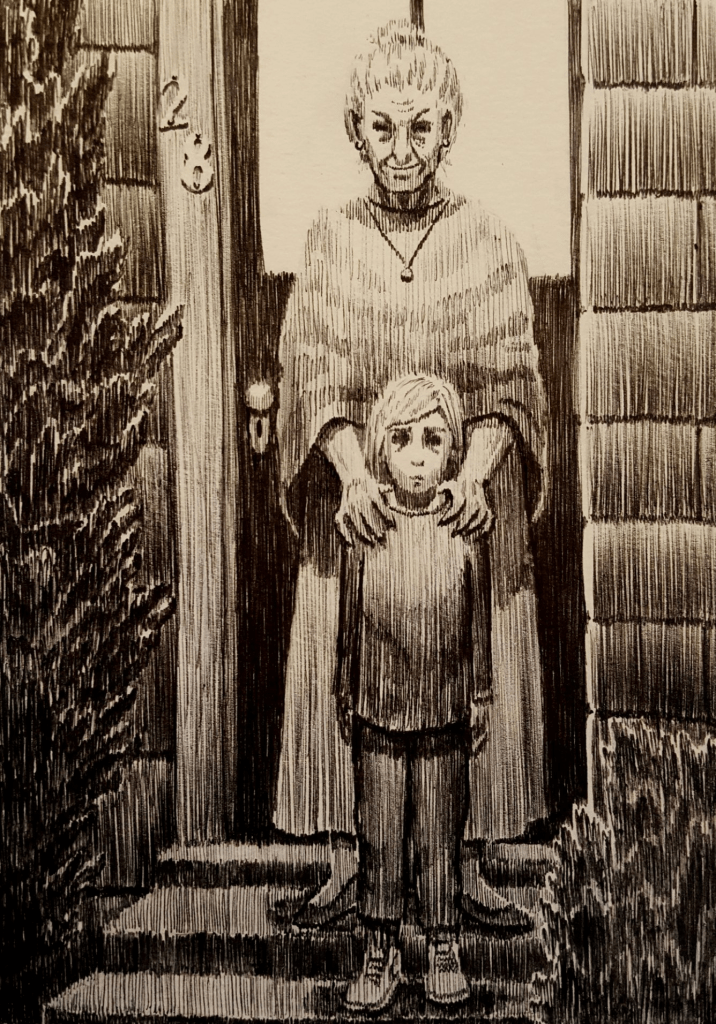

Grandpa was a big man. I’ve been told he was six-foot-four, but to me he was more like the Colossus of Rhodes. He wasn’t made of bronze, like the original, but heaps of hard muscle, wrapped in layers of thick winter fabric.

He was always kind to me, but I later learned that he’d mellowed in his old age. Eventually, Dad told me a few things about his own childhood, and some of them were hard to hear. Back in the fifties, Grandpa drank spirits in the day and sometimes beat his children. He even beat his wife when she tried to intervene.

I never met Grandma because she bailed on the marriage, running away in the middle of the night. No note—nothing. No one had heard from her since, and I know that hurt my father very badly. He was only ten at the time and used to drive himself mad, trying to work out what he’d done to let her down or disappoint her. After doing her best to protect him, she’d simply walked away with no explanation. Apparently, once it became clear that she wasn’t coming back, Grandpa had sworn off the booze entirely and slowly rebuilt his relationship with his children.

It’s hard to reconcile these facts with my own memories of Grandpa. The man I knew was a gentle giant with a wry sense of humour. When he smiled, his mouth barely moved but his eyes sparkled, like two bright coins on a crumpled chamois leather. I couldn’t imagine him ever getting drunk, let alone violent. In the morning, he smelled of coal tar soap and aniseed toothpaste, and at night he smelled of Old Holburn. Even today, these are smells that make me feel safe. I thought he’d be around forever—but he was an old man, of course—and how could he be?

One day, when I came home from school, it was clear that something bad had happened. Mum and Dad were talking in low voices. When I entered the hall, they retreated further into the kitchen, quietly closing the door.

At last, Dad emerged.

“Do you want to knock on Grandpa’s door,” he said—trying to make it sound like a bit of a game—“and walk the dog yourself tonight?”

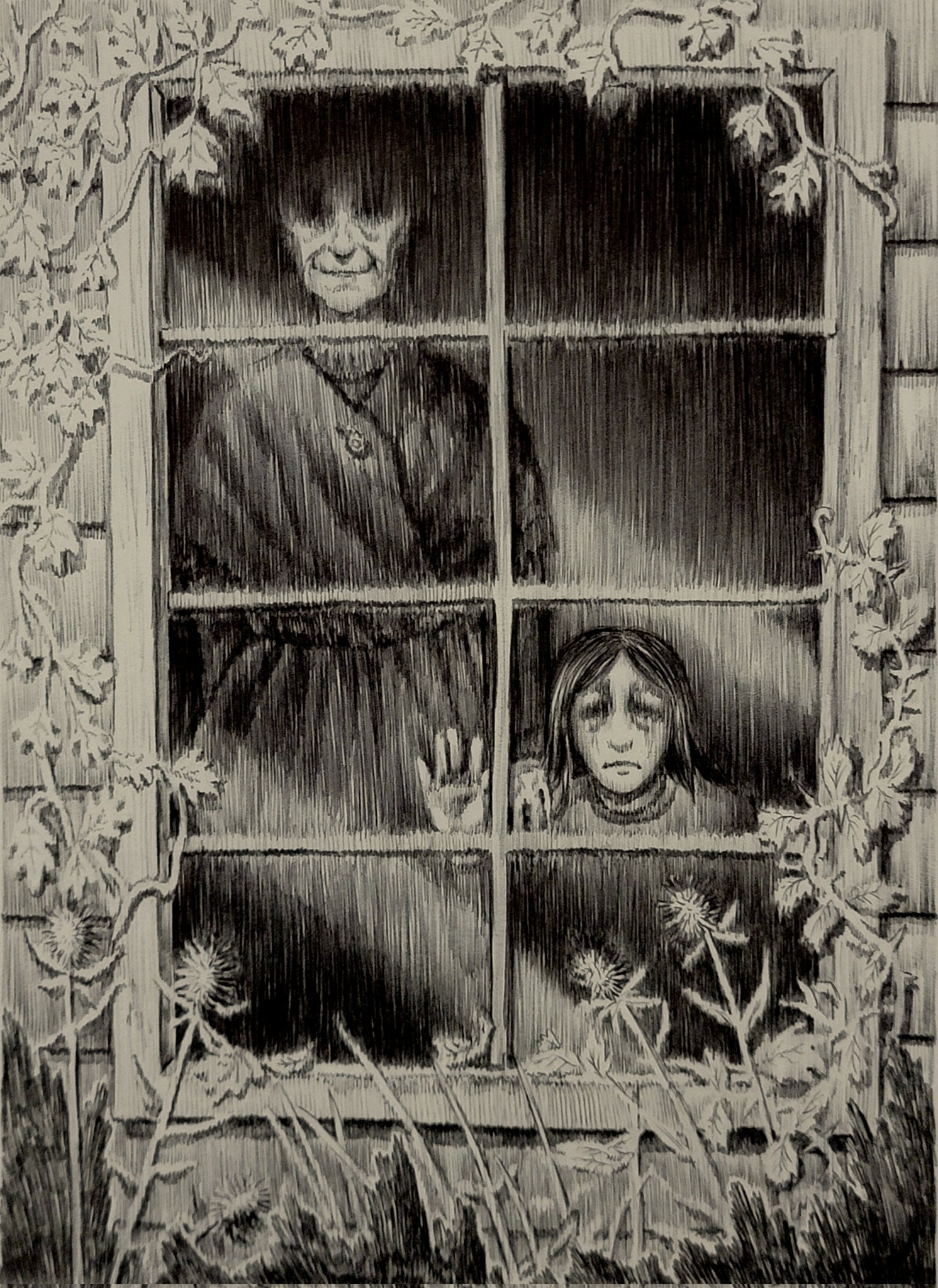

It wasn’t Grandpa who answered the door but Auntie Jill. From that point on, it was my job to walk Din-Dins, and I did it alone. I don’t know what happened to Grandpa—whether he’d had a fall, or whatever—but I don’t think I saw him standing after that. He always seemed to be sitting in a chair, shrinking in on himself.

When Autumn came, he was moved to a nursing home. It wasn’t long before Dad took me to visit. The lobby smelled of gravy granules and disinfectant. There was a communal hall with pretend carpet laid down in squares, and the armchairs were like the ones in a hospital. There was something about it that made me uneasy, so I held back nervously.

“Come on,” said Dad impatiently.

We found Grandpa watching snooker with the sound turned down. Dad verbally reminded him of all the nice things he got at the nursing home, like fish on Friday, roast beef Sunday. They’d watched a tape of Brief Encounter. There was even a chess set by one of the windows, though one of the pawns was a cork stood on end.

“It’s not bad, is it?” said Dad. “I mean, all things considered, it’s not too bad.”

Grandpa smiled but not with his eyes.

“It’s not too bad,” he agreed.

When we got back in the car, we sat there quietly for a moment.

“Grandpa’s not all right,” I said at last.

Dad looked at me in the rear view mirror.

“What do you mean, ‘not all right’?” he said in alarm. “He was smiling, wasn’t he?”

“Well yeah. But not properly.”

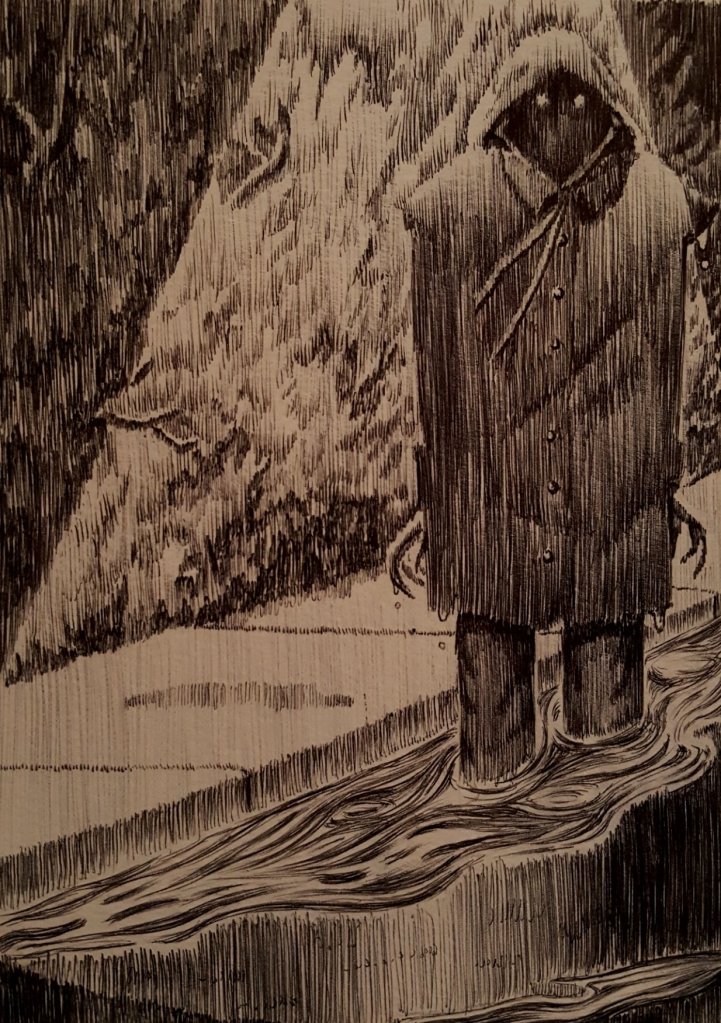

I didn’t have to worry about Grandpa for long. On the ninth of December, when the first specks of snow were swirling in the air, he went to sleep and never woke up. He was laid to rest in St Paul’s cemetery, on the edge of Kersal Moor. Din-Dins died a week after that.

Four years later, it was 1995 and I was sixteen. The winter solstice fell on the twenty-second of December that year.

I kept looking at the moon in the nights leading up to it. Over the course of a week and a half, it slowly waned to a cold sharp curve. On the twenty-second of the month it vanished altogether.

I went to Moor Lane and found the path by St Paul’s Church. It led from the road into utter darkness. I walked down it, beginning to stumble as I left the familiar glow of the orange street light. On the moor itself, there were humps of long grass to trip me up and patches of grit where the soil had worn away.

Eventually, I found my way to the highest part of the moor and stood there in triumph, looking all around me. As dark as it was, the horizon was jewelled with city lights, especially when I looked south-southeast towards Manchester.

“Hello?” I called.

Nothing came back from the darkness. All I could hear was the sound of cars on Moor Lane. As I waited, they became less frequent and eventually stopped.

“Hello?” I called repeatedly.

Just as I was about to give up and go home, I heard it. Soft and tuneless, like a faraway football chant.

O, unless you are a vicar

Hell will have your soul for sure…

My heart quickened. It was so faint I cupped my ears and held my breath to listen. I resisted the urge to shift my weight in case it made the grass rustle underfoot.

O, unless you are a vicar

Hell will have your soul for sure

The Devil’s quick but we were quicker

Now we hide on Kersal Moor

I looked in the direction where it seemed loudest. I wasn’t sure if my eyes were playing tricks on me, but I suddenly thought I could see the ghosts. I wasn’t scared because it felt like a dream. This is real, I kept telling myself—but I couldn’t make it stick. The song continued:

“Via, veritas, et vita”

Says the guard on heaven’s door

But no one has to face Saint Peter

If they hide on Kersal Moor

They shuffled towards me as they sang, making their way up the long dark slope. As they came closer, I no longer had to concentrate to hear them. Their voices made me shiver in the night.

Butcher, baker, barrel-maker

Hunter, hatter, even whore

No one has to meet his maker

In the dark of Kersal Moor

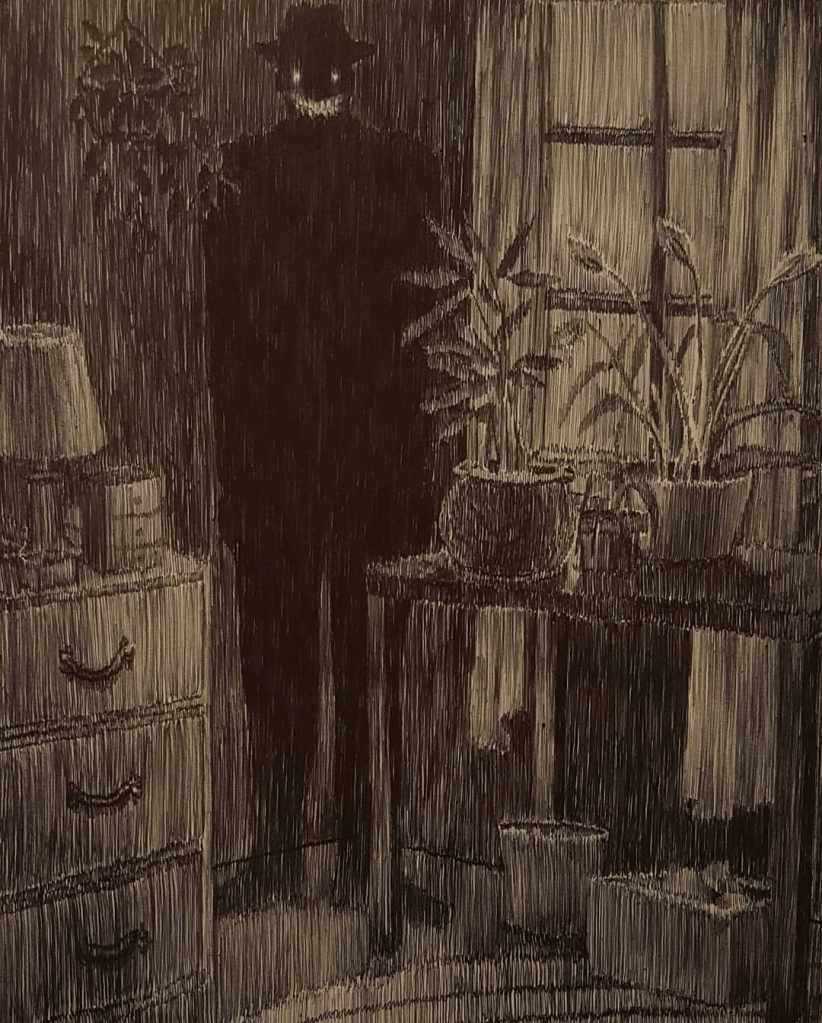

By the time they finished singing I could see them quite clearly. They had long hungry faces with sunken cheeks and hollow eyes. Their features had no colour, as far as I could see, or even substance to speak of. It was like they were etched on the dark in faint grey glimmers.

“Gather round!” cried a voice in the dark. “Gather round!”

One by one they joined me on the dark summit. In that eerie crowd, lord and leper stood shoulder to shoulder as equals. I thought I could make out their clothes, or maybe just the memories of clothes, conjured out of nothing. A greatcoat here and a flat cap there, knitted from the threads of the night itself.

“Silence!” called the ringleader.

I turned to look at him and started with surprise. His neck had been cleanly severed. He carried his head like a football, holding it aloft to project his voice.

“Do you fear the hereafter?” he began. “Have you been a sinner? Are you willing to face God and the Devil, and risk your immortal soul?”

“I—I don’t know,” I said honestly.

A murmur of concern rose from the crowd. Their leader looked disapprovingly down at me, then stamped his foot for silence.

“Swear the oath instead!” he urged. “Take the pledge! Promise to join us when you die! Spend eternity here, on the moor!”

The ghosts began to sing again. This time, the chorus had a more urgent quality. It was almost a touch of menace. I scanned their faces in wonder, looking for signs that they were happy with their chosen afterlife. I couldn’t see any. Just a nagging kind of hunger, and a deep yearning for something lost.

Then I saw him.

A familiar face like chamois leather, looming over those of his neighbours. He hadn’t changed at all—or rather, he’d only grown fainter. He was singing with the rest of them, and when he saw that I’d spotted him he nodded in encouragement and smiled.

But not with his eyes.

“Grandpa?” I said in surprise—but he melted back into darkness, singing as he went.

I turned my attention to the ringleader. He lowered his head until the pale face was level with mine.

“Swear!” he bellowed.

His breath was a rush of cold air, like a bitter wind blasting my face. As I staggered backwards, my dreamy fascination turned to alarm. I’d seen and heard enough, but when I looked behind me I saw no escape route. I was surrounded on all sides by ghosts.

“Swear, swear!” they chanted.

They began to close in on me. As they did, I span helplessly on the spot, then turned skyward in desperation. Nothing could be seen. No stars—no clouds—nothing. Not even the faint grey glow of light pollution. There was nothing left in the world but me, the ghosts and perfect darkness.

“Swear!” they screamed in chorus.

“I don’t want to,” I begged.

I covered my ears and sank to the ground. A howl of disappointment went up around me, ringing in my ears.

The story ends exactly where I left it. I must’ve passed out—or maybe woke up?—because the next thing I knew it was morning. The long brown grass was wet with dew. The silver sun was creeping up the sky. The ghosts were gone from Kersal Moor.

I’m forty now. People tell me I look older.

I wouldn’t say I believe in ghosts, exactly, because I waited a long time on the moor that night. Maybe I just fell asleep and had a nightmare. I don’t think I did, but it’s certainly possible.

The next winter solstice to fall on a new moon was the one at the end of 2003. I don’t mind saying I was too scared to leave the house that night. I just sat in the kitchen with a six-pack of beer, praying that I wouldn’t hear them singing from the nearby moor. It happened again in 2014, but I’d moved to Bristol by then and didn’t feel as threatened.

The words of the song were:

O, unless you are a vicar

Hell will have your soul for sure

The Devil’s quick but we were quicker

Now we hide on Kersal Moor

“Via, veritas, et vita”

Says the guard on heaven’s door

But no one has to face Saint Peter

If they hide on Kersal Moor

Butcher, baker, barrel-maker

Hunter, hatter, even whore

No one has to meet his maker

In the dark of Kersal Moor

Tell me, have you been a sinner?

There’s a loophole in the law:

Meet us where the veil is thinner

In the dark of Kersal Moor…

The next winter solstice with a new moon will be on 21 December 2025. When it happens, I know I’ll be far from Kersal Moor. I hope you’ll follow my example.

In any case, I try not to think about it. If it was real, then Grandpa must be stuck on the moor forever. I know it’s not good there. He was singing and smiling with the rest of them, but I could see it in his eyes. He’s not all right.

And when I remember his face, I can’t help but wonder: why did he say yes? Why did he take the pledge? What had he done in his life, to be so scared of God’s judgement?

I mean, don’t get me wrong—I know he used to drink and beat my father—but didn’t he make amends? Why did he choose eternity on Kersal Moor, rather than taking his chances with Heaven and Hell?

And then I always think—what really happened to Grandma?

Ellis Reed, 30/05/2025