“Deep Summer Magic” is also available as a free audiobook, narrated by Nick Denton.

It’s strange how long that summer seemed. We were fourteen that year. The days buzzed around us like a swarm of midges. The long holiday stretched out before us, as bright and as wide as the River Nile.

There was a gang of us who knocked around together. We weren’t popular at school, but—with the possible exception of Tim—were far from the bottom of that brutal pecking order (Tim had the distinction of being very large but very soft, with a lisping voice that hadn’t really broken). Aside from Tim, there was Jon Jones, who was pretty tough; “Mandy”, or Tom Manders; and finally me. We’d bonded over a love of electric guitars, 80s horror movies, and video games like Mortal Kombat.

One day in August, there was a heatwave, so we decided to camp near the river in the park. I don’t remember who said it first. I don’t even think it was our idea. It was simply there, humming in the hot air, till someone gave it voice.

I remember I’d been lying in bed some nights before. The window was open. The air was warm and almost still. Out in the dark, something made a soft knocking sound, like coconuts or bits of wood. I couldn’t tell if it was a nearby tapping or a distant pounding, but whatever it was seemed to call me from my bed, urging me to rise and rejoice.

I was in the fairyland at the edge of sleep. As my thoughts turned to mush, I pictured a girl running through the dark valley, banging two sticks. Come and play, she seemed to call. Come and play. The river ran beside her like a friend. Then I was asleep.

The next day, we gathered at the top of Moor Lane and hurtled down it on our bikes. Halfway to Kersal Vale, one of us cried, “Let’s go camping!” Maybe it was me.

None of us had tents but it didn’t seem to matter. We’d been sleeping with our windows open and the covers off, so were just as happy to kip in our clothes on a bit of soft grass. The plan was, Tim and I would tell our parents that Mandy was having a sleepover. His mum was dead and his dad was in prison, so he lived with an adult brother in Kersal Vale. “Big Mandy” was far from neglectful, but he was a brother rather than a dad, and more than happy to cover for us.

Jon didn’t need to make arrangements. His parents were spending the night in Burnley because his grandma was starting to struggle. They’d been doing it more and more since she’d had her mini stroke. When school started, Jon wasn’t coming back, because they were getting a place in Accrington. On the last day of term, he even got us to sign his shirt, like the fifth-years do when they’re leaving forever.

Just as the sun was setting, we gathered at the bottom of Rainsough Brow, on the corner of the junction with the mini roundabout. There were no mobile phones then, so we’d planned the rendezvous on our landlines—which, looking back, seems as quaint as using walky-talkies, or whispering into tin cans. These were the days when you knew your friends’ numbers off by heart, because that was the only way to talk after school—short of going round in person—and you had to dial the numbers by hand.

“Right,” said Jon. “Did you all bring torches?”

We had. Poor Tim’s was more of a toy than a proper torch, so we spent a good few minutes taking the piss out of him.

“And what about food?”

We opened our rucksacks for inspection. I’d made tuna paste sandwiches and wrapped them badly in clingfilm. I’d also nicked some Mars Bars from the cupboard and filled a bottle with Ribena. Tim had brought literally nothing but a twin-pack of Bourbon biscuits, which cost about 20p from Tesco, so we jeered at him again. Mandy had three different types of cake bar, and—this also got some jeers—a single bag of prawn cocktail crisps, which had popped in transit.

“Good,” said Jon.

Then he smiled and unzipped his bag. Instead of food he had three big bottles of cider. He also had two packets of cigarettes, though one was open and looked a bit crushed.

Mandy whistled appreciatively. Tim looked around nervously, as if we might get arrested. Then we zipped our bags up and made our way to the nearby park.

The park follows the river, all the way to Whitefield at least. It’s funny how much green there is, so close to the greys of suburbia. You can walk all the way from Rainsough to the big Tesco in Prestwich, and it’s river almost all the way. Within minutes of leaving the mini roundabout, it was like we were in the middle of nowhere.

“Funny how close we are to the country,” said Tim.

Jon snorted.

“It’s not the country, you pillock. It’s Drinkwater Park.”

“I know. But it’s like we’re miles from anywhere.”

“Yeah. Thank F░░░ for all them Bourbon biscuits, eh?”

We laughed but knew exactly what Tim meant. We were following the river north and could have been anywhere on Earth. Water shone to the left of us, mixing colours from the sky with the faint green tinge of chlorophyll. The river made a soft liquid sound, lapping the grass that grew on its banks. Birds twittered in the dying light.

Before long we had to use our torches. We swung them in the dark, watching shadows lean in and then draw back. Our conversation dwindled, till all we could hear was the plop-plop-plopping of the river.

Then, once more, there came that strange knocking sound. It could have been soft and near or loud and far, but it made me shiver—in a nice way, I mean—like the thought of a coming birthday.

“What’s that sound?” I wondered.

They all knew what I meant.

“Dunno,” said Mandy. “But I like it.”

It was a strange thing to say, but I knew what he meant as well.

Later in life, it became important for me to work out exactly where we were that night. I know we hadn’t got far because we kept mucking around. At one point, we were chasing Tim, flashing torches in his eyes and trying to make him have a seizure. We stopped for sandwiches and some of the cake bars. I know we’d gone past the prison, because Jon made fun of Mandy’s dad—and I know there was a bridge, because Mandy did a piss off the side of it. We were a short way past the bridge, and that’s all I know for sure.

“It’s spooky at night,” said Mandy.

To lighten the mood, he shone his torch up his chin and did a manic laugh.

“Does anyone know any ghost stories?”

“Nah,” said Tim.

He was trying to sound blasé but I knew he was nervous. He was visibly relieved when Jon—the de facto leader of the gang—scoffed at the suggestion.

“It’s not a bloody cub camp,” he said. “Let’s have some cider and smoke these fags.”

He balanced his torch and got the bottles out. We passed them around, wincing at the sharp taste. Then he tried to light a cigarette, holding it over the lighter like a candle.

“You’ve got to put it in your mouth,” said Mandy.

Jon scowled.

“Does it matter?”

“Yeah. You’ve got to suck it. If you do it like that, you’re just toasting it.”

Jon tried it Mandy’s way. When it worked, he coughed out a cloud of smoke.

“Oh yeah,” he muttered.

He tried a second time and managed to get it down. It came out in a long shuddering breath, like he was on the verge of coughing again.

“Tastes pretty good,” he said, trying to save face—but it was a ridiculous thing to say—because it was a Lambert & Butler, rather than a Romeo y Julieta.

We all smoked except for Tim, who reminded us piously that “Gramps” had died of lung cancer. Jon pointed out—not unfairly—that “Gramps” had been eighty years old, and twenty stone if he weighed a ounce. All things considered, Gramps had had a pretty good innings.

Eventually, feeling a bit sick, we finished the cigarettes. Mandy checked his watch.

“It’s still early,” he said. “Should we carry on walking?”

“Nah,” said Jon. “We’ll end up at Tesco’s if we’re not careful.”

He turned his back to the river and shone his torch through the trees. We could hear the knocking again. It seemed to come from the other side.

“Let’s explore,” he decided.

We made our way through the dark trunks, snagging our jeans on brambles. Soon we were lost in a wild wood, glimpsing stars through the broken canopy.

“We’re nearly through,” said Tim.

Ahead of us was a dark building, blotting out the sky. Even in the moonlight, you couldn’t see much except for the size. We emerged from the trees and hurried over, shining our torches this way and that.

“Where are we?” I wondered.

Mandy shrugged.

“Dunno. Looks empty.”

It was a Georgian manor with tall sash windows. In the dark, they were bars of chocolate stood on end. Some of the panes were smashed. The house was made of brick but had a stone porch, with two pillars and a pediment.

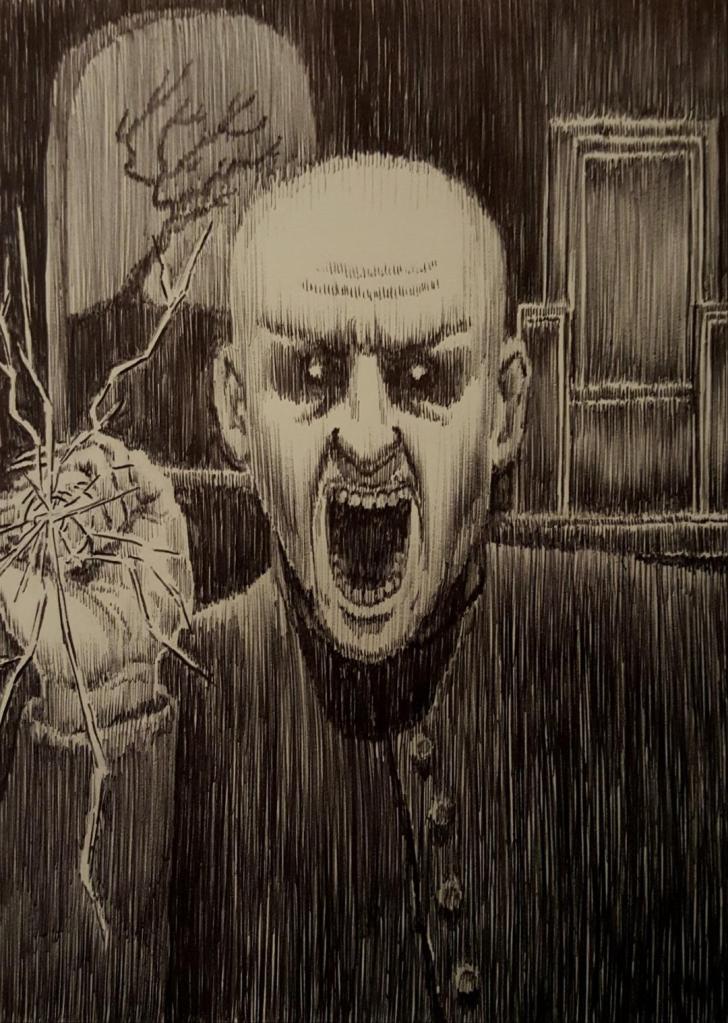

I shone my torch around. Whatever it was, it didn’t seem real. Torches have a funny way of destabilising things. I think it’s the moving shadows. Ripples of chiaroscuro, spreading like a strange liquid.

“The door’s open,” I realised—shining my torch.

“We’re going in,” said Jon.

Tim looked at him in horror.

“Don’t be daft,” he begged. “It’s trespass!”

Mandy and I looked at each other. We had to pick a side. We didn’t want to go in the old house, but the alternative was joining a tragic faction led by Tim.

“We could call through the door,” said Mandy. “If no one answers—it’s probably safe to look around?”

I shrugged. It seemed like a fair compromise.

“Okay,” I agreed. “Do it.”

Jon marched up to the open door.

“Hello?” he called. “Hell-o?”

No one stirred inside, so he took a deep breath.

“Scrubby-dubby-doo-oo-o!” he bellowed at the dark.

We burst out laughing. I can’t tell you what “scrubby-dubby-do” means, because it doesn’t mean anything. It was just something we liked to shout. Mostly at Tim, when he turned up in his dad’s old clothes, or a horrible pair of trainers.

Satisfied, we went inside. The laughter soon died on our lips. There’s something instantly sobering about an old building. A stark memento mori that can’t be put into words.

We found a long dark lobby, with evil-looking stairs that rose into gloom. Mud had been trodden inside, drying on the tiles in brittle shapes. Grey dust hovered in the air and stuck to the banister. There was a red carpet on the stairs, held in place with stair-rods—but the carpet had been eaten by moths, and the rods were discoloured with age.

“It’s not abandoned,” Tim realised.

“Of course it is,” said Jon. “Look around.”

“I know—but listen.”

We did. It was clear from our faces that we couldn’t hear a thing. Then Mandy’s eyes widened.

“A clock,” he said. “I can hear it ticking. Right?”

“Exactly,” said Tim. “Someone’s been putting batteries in.”

I could hear it too. It was a deep tock, tock, like someone clicking their tongue at the top of the stairs. The sound of an antique.

“Or winding it up,” I pointed out.

Jon rolled his eyes.

“Well whoever it was, they’re not here now,” he said impatiently. “And we shouldn’t leave till we’ve seen upstairs. Come on.”

One by one we mounted the stairs. With every step we took, they groaned underfoot.

“These stairs are loud,” said Mandy. “Hope they don’t collapse!”

“It’s not the stairs,” said Jon. “Tim’s got creaky trainers.”

“Give it a rest,” Tim muttered.

At the top of the stairs we found a long dark hall. The landing wasn’t bad, but the bottom of the hall was a real mess.

“That ceiling’s going to fall,” I said glumly.

Down the ruined hall, doors stood in pairs, facing each other like soldiers. All were closed except one at the far end which was slightly ajar.

I probed the dark space between door and frame. I felt like I could push it open with the beam of light.

“Is this what’s ticking?” said Mandy behind me.

I turned. He was shining his torch at a grandfather clock.

“What’s the time?” I wondered.

“Dunno. It’s not right.”

He checked his own watch.

“Half ten,” he added.

Tim glanced at the clock.

“It’s not that,” he said. “It’s coming from over there.”

He waved down the hall.

“And I think I was wrong. I don’t think it is a clock. It’s the sound we heard outside. The weird knocking.”

I cupped my ear. I couldn’t tell if he was right or not.

“I actually heard it in bed,” said Mandy. “The knocking, I mean.”

“Me too,” I said.

“Me too,” Tim agreed.

Jon groaned and sat down.

“Me too,” he said. “Come on, let’s have another drink.”

Tim looked at him in surprise.

“Here? Are you kidding? Have you seen the state of it? We’re probably breathing all the spores in! Can’t we just go now?”

When no one answered, he shook his head in annoyance.

“Right,” he said bitterly. “I’ll see you outside then.”

He turned to leave. When he was halfway to the stairs, the knocking got faster and louder, making him pause.

Knock-knock-knock.

My skin crawled in a pleasant way. A small electric thrill. I suddenly knew how the ancients felt, when the shaman banged his trance-inducing drum.

Knock-knock-knock.

Jon sprang to his feet.

“It’s in that room,” he realised. “The one at the end. Someone’s mucking around.”

He took a step forward.

“Who’s there?” he called.

The knocking stopped abruptly.

“I am,” said a voice in the dark.

Tim jumped in fright, but the rest of us were just confused. It was the voice of a girl, coming from the room with the half-open door. The stranger thing was, the room wasn’t lit—so whatever she was doing, she did in the dark.

“What are you playing at?” said Jon.

“Banging sticks.”

She did it once for illustration. Knock!

“You were by the river,” said Jon.

“No.”

“Then how did we hear you, by the river?”

She laughed softly through the crack in the door. As she did, the end of the hall seemed visibly to darken. Liquid gloom was seeping out of there. It was like a cloud of octopus ink.

“How did you hear me in your beds?” she pointed out.

When we didn’t answer, she resumed her game. Knock, knock, knock.

“They’re special sticks,” she said through the door. “The sound they make is the heartbeat of the soil. The rhythm of the rain. Deep summer magic that only I know. The sound is heard where I wish it to be heard.”

Knock, knock, knock.

My heart soared. Suddenly, there was nothing to fear from the end of the hall. The dark was a friend and not a threat. The mould on the walls wasn’t squalid: it was the miracle of life, nourished by rain that remembered the sea. It was ripe and wholesome, like a field of wheat in summer.

“Come and play,” she called from the dark.

As if in a dream, we began to walk to the end of the hall.

I got there first but paused at the door, staring in a sort of trance. It was Jon, our glorious leader, who pushed his way past and shone a torch inside.

To this day, I can’t remember much about the room itself, except how dark it was. I dimly recall the black mould and maybe a window. That’s it. I couldn’t tell you if the room was big or small, furnished or bare. All I really remember is the girl.

She was standing in the corner with her back to us. Her hair was full of twigs and dead leaves. She wore a long white gown and her feet were bare.

Knock, knock, knock, went the sticks in her hands.

She didn’t stop or turn round. With each percussive blow, her elbows twitched at her sides.

We looked at each other in pleasant confusion, then turned our gaze to the girl.

“Who are you?” Jon marvelled.

“The spirit of the woods,” she said. “You can stay with me forever in this house.”

“Then show us your face,” he urged.

“You don’t want to see it.”

He moved impatiently towards her.

“Yes we do.”

I don’t know how the spell was broken, but I know I wobbled as I stood there. Did we want to?

It was suddenly strange, rather than charming, for the girl to be standing with her back to us. I wondered what she was doing there at all. Before we’d brought our torches, she’d been waiting in the dark. Her bare arms were those of an old woman, even though she had the voice of a girl.

“Show us your face,” said Jon again—reaching out to grab her shoulder. I realised, with a sudden pang of dread, that I didn’t want to see it.

Tim was the first to bolt. Without a word, he turned and fled. Mandy and I followed him through the hall, all the way down the dark stairs. His thumping feet had stirred us from our trance.

Jon didn’t follow.

We heard a bloodcurdling scream behind us. It grew in volume as we exploded through the door and into the night. It followed us through the dark trees, all the way to the river.

We got split up in the dark but managed to find our separate ways home. I remember I came out of the park somewhere in Prestwich, then wandered aimlessly till I found Bury New Road.

In the days that followed, we talked by phone, speaking in low whispers so our parents didn’t hear. None of us could reach Jon. To this day, I have no idea what happened to him. Maybe his parents returned from Burnley to find him missing, but news never reached us, because he’d already left school. It does seem odd that the police wouldn’t speak to his friends, so I like to think he found his way home, and they moved to Accrington as planned.

Later in life, I tried to find him on social media. I never could.

Nor could I find that house again. As an adult, I viewed the whole park on Google Maps. As far as I could see, there was no Georgian manor.

One day, I returned on foot and tried to retrace my steps. Somewhere past the prison and the bridge, I turned my back to the river and went through the trees. After a while, I found the bare foundations of a long-gone building.

I did a bit of reading online. I believe they were the remains of Irwell House. According to Wikipedia, “the house caught fire during a civil defence exercise in 1958 and was demolished some years later. The foundations and the first course of stones were left in place and are still visible today.”

I’ve since found a painting of Irwell House, so I know it was a Georgian manor with sash windows. The doorway was stone, with two pillars and a pediment. It came down years ago, before I was born. The foundations are wild with long grass. Make of that what you will.

I don’t know who the girl was, but I know she isn’t human. Maybe she never was—but she’s out there, somewhere. Even now, she haunts a dark hall in a house that isn’t there, calling children in the night.

When summer comes, I leave a TV on in my bedroom, for fear I’ll hear that knocking again.

One thing remains to be said. When I left Kersal High for the last time, I got the other pupils to sign my school shirt. That was the tradition.

Years later, I found it in the loft and read the messages. One of them surprised me.

I’m still here, someone had written. Come and play. Jon.

I hope it was Tim or Mandy trying to be funny, but in my heart of hearts I know it wasn’t.

Ellis Reed, 19/04/2020