Image by Marisa Bruno

I grew up in Broughton, near the cottages and long cobbled streets of the cliff.

The cliff was a conservation area, which meant that Salford City Council watched it like a hawk. Here and there, you would find sage-green Victorian lamp-posts, or the ghosts of old tramlines cutting through the road. Relics such as these were sacred to the council, who did everything in their power to preserve them. There was also an actual cliff there—hence the name—but it wasn’t much of one. Just a steep sandy drop, carved out by the bend of the river. Every now and then, another bit of street went sliding down the slope, and more of the old tramline was lost forever. As a result, and despite the best efforts of the council, the whole neighbourhood was essentially doomed.

We often walked that way, Ruth and I. We would stroll through it till we reached the bollards at the end of Cliff Crescent. Then we would go our separate ways. Mine up Bury New Road, hers across Northumberland Street.

There was nothing for us to do round there, but I suppose we liked the atmosphere of the place. The cliff itself had a strange quality that our young minds couldn’t quite process, and the impression it made was all the more profound for being inexpressible. When we peered across the concrete barrier, we saw how the ground simply fell away, and it made us feel as if the whole of the human world, which normally seemed so solid and durable, was actually fleeting and ephemeral. I think we just liked to be there, so we could soak up the feeling of impermanence.

I remember the two of us walking down it one evening in June. I was thirteen that summer and so was she. As dusk began to fall, we found a house that we’d never seen before, and I remember how we slowed to a halt and just stood there for a while, admiring the front of it. The whole house was filled with amber light. There was so much light it overflowed the windowsills, making the drive the colour of Lucozade.

“It’s like a magic cottage,” I said in awe.

We basked in the orange light, wondering how it was possible that we’d never seen this beautiful house before. Then Ruth solved the mystery.

“We have seen it before,” she realised. “Lots of times. It was a complete wreck, wasn’t it? They’ve done it up.”

As soon as she said it, I knew that she was right. The last time we’d walked along the cliff, the house had been little more than a shell, with wild brambles flooding the porch. All but one of the windows had been boarded up. Since then, someone had completely renovated it, and I was surprised that they’d done the work so quickly.

“You’re right,” I said. And then, more shyly: “Do you think we’ll have a house like that?”

She smiled at me.

“May-be,” she said teasingly—“if one of us wins the lottery!”

Before I could protest—because I planned to get rich on my own merit—the front door clicked open, and we watched in surprise as it swung soundlessly ajar.

Orange light poured from the crack. It seemed to waver slightly, as if something was stirring in the bright hallway—just out of sight—casting long ripples of shadow.

“Come inside,” called a woman’s voice from the hall.

Ruth instinctively moved to obey, but I restrained her arm.

“Don’t,” I said quietly. “We don’t know who it is.”

She looked at me in surprise.

“What do you mean? It’s person who lives there.”

“It’s just—creepy.”

“Come inside,” called the voice again.

I ignored it and tried to lead Ruth away, but she shook me off in irritation.

“It’s just the new owner,” she said. “She probably wants to show her house off to someone.”

“Come inside,” called the voice a third time.

The repetition didn’t sit well with me. The woman in the house hadn’t added anything, or explained anything. She’d just said it again. And there was something uncanny about it. The repetition, I mean—like the not-quite-human voice of a parrot.

“Ruth?” I said nervously.

The orange light was getting brighter and brighter. She almost seemed hypnotised by it.

“I’m going inside,” she said at last. “You don’t have to come with.”

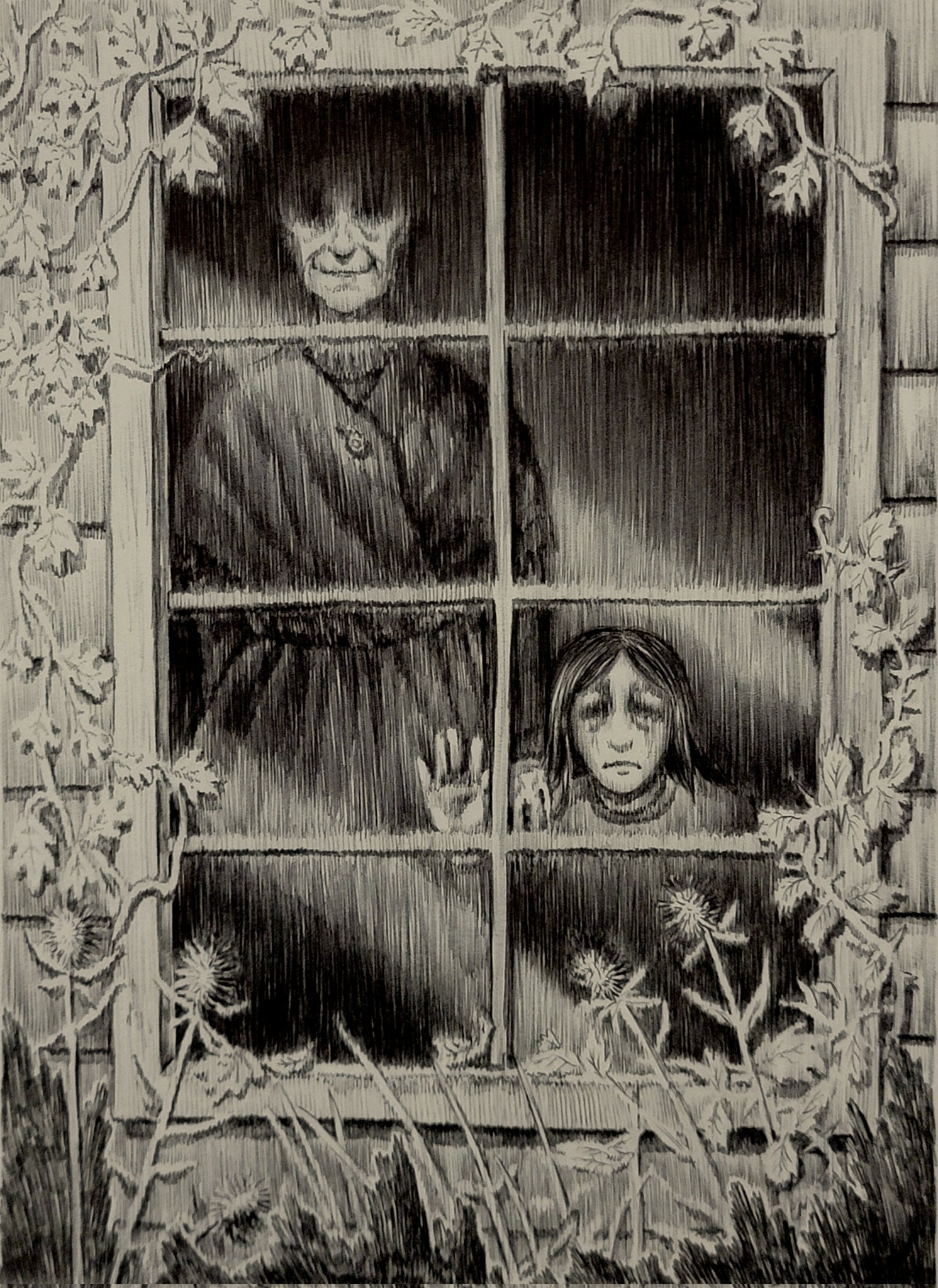

As she marched up the drive, I glanced at the first floor windows. One of them wasn’t lit like the others. In the gloom beyond the glass, I could see the ghostly outline of an old woman looking down at us.

“Ruth,” I said more urgently.

The top of the woman’s head was wholly lost in shadow, but I could just about see the bottom of her face. The white contour of her chin, and the small triumphant curve of her mouth.

“Ruth!” I started to beg—but it was too late. I watched her enter the doorway, and saw how she seemed to dissolve in the orange light. I remember that very clearly: she seemed to dissolve in the orange light. The door shut at once behind her, and I thought I heard a faint malicious laugh from above.

“Ruth?” I called a final time—but the spell was broken. I rubbed my eyes in confusion. It felt like I was waking from a dream. There was no orange light, I realised; just the faint blue gleam of nightfall.

When I looked at the house with fresh eyes, I saw that it hadn’t been restored at all. Brambles flooded the porch, just like before. All but one of the windows were boarded up. The one that wasn’t boarded up, I now realised, was the one on the first floor, where I thought I’d seen the old woman. But was that just a dream?

“Leave now,” the wind seemed to sigh. “Leave forever.”

The whole thing had been an illusion, but Ruth was still gone.

I fled the scene in confusion. And poor Ruth, she was never seen again. Except maybe once—but I’ll come to that in due course.

The adults knew that Ruth and I were sweethearts. As a consequence, when she never came home, they wanted to speak to me. First my parents—then her parents—then the police.

I simply feigned ignorance. It was easy to pretend that we’d gone our separate ways at the bollards, like always.

For a short time, they actually had a suspect, because there was someone nearby with the right kind of criminal record. Nothing came of it, of course, because he had nothing to do with it. They released him without charge, and after that there were no more developments.

As far as I know, Ruth’s disappearance is now classified as a “cold case”.

I went back there once, years later. I was dismayed to find that the derelict house was still standing. As before, all the windows were boarded up, except for one on the first floor. When I looked up at it, there was a moment—a fleeting moment—when I thought I saw Ruth looking out from the glass. Help me, her eyes seemed to say.

She wasn’t alone. An old woman’s hand lay protectively on her shoulder. The top of her head was lost in gloom, but I could still see the bottom of her face, with that same triumphant smile.

I don’t visit the area any more.

Sometimes, I’m troubled by the thought that Ruth will be trapped in that house forever, shut away with the ghostly woman who lured her inside.

But then I remember how the river still sweeps across the land, carving out a valley, eating at the edges of suburbia. I remember the cliff, and console myself with the thought that the whole conservation area is doomed to go tumbling down it.

When that happens, nothing will remain of the derelict house.

Not even the ghosts.

Ellis Reed, 04/11/2023