When my son was young, something happened in the night that we never discuss.

I don’t know if he remembers it. Some days, I’m not even sure it really happened.

But when it’s late at night and I can’t sleep—when I open my eyes to the lukewarm pressure of the dark—I remember what happened with a cold thrill of fear, and wonder if I’ll ever sleep soundly again.

Sebastian was a nervous child. I never knew why, but I always used to worry that it was somehow my fault.

I split up with his mother when he was six. There wasn’t much anger by then. We almost laughed at the state of it. I remember that we opened a bottle of wine and stayed up late to sort it all out.

But afterwards, I kept feeling like we’d ruined his whole childhood by failing to make the marriage work. Every time something went wrong in his life, I pictured the divorce as a dark figure standing over him. Like the opposite of a guardian angel, rubbing its hands with glee.

Maybe I’m being too hard on myself. That’s just my personality. My least favourite song is the one that goes non, je ne regrette rien, because the truth is I regret almost everything.

When Sebastian was ten, I still had to tuck him in at night. He had a superstitious terror of his own wardrobe and wouldn’t sleep unless I checked inside it for monsters. Even then, he had a lamp by his bed, and it had to stay on through the night.

To be fair, it was a scary wardrobe. A big solid unit, with a crest along the top that seemed to scowl at you.

It had once belonged to my mother-in-law. After she died, my ex thought that Sebastian would like it. He didn’t. I got him the Narnia books, hoping that he’d warm to it. He just got scared of witches.

By this point, I was starting to worry that he wasn’t as brave as the other boys in his school year. And to be honest, that bothered me. But I could sympathise, too. If there’s one thing that gives me goosebumps, it’s the thought of the supernatural. Even as an adult, I’ve been known to hurry out of a dark room, if I go in there alone and suddenly get the willies.

The funny thing is, apart from that, I like to think I’m quite brave. For instance: after the divorce, I took up free climbing. Every bank holiday, I drove to Land’s End or Malham Cove, just to see how high I could get without any gear. I was quite happy with my fingers and toes on the rockface, and nothing but fresh air under my feet.

Before Sebastian was born, I even passed selection for 4 Para, which is the reserve unit of the airborne infantry. I don’t want to overegg it because I didn’t deploy, so I’ll never know if I had it in me to be a soldier, but signing up for the reserves, and jumping out of planes, aren’t the actions of a nervous man.

Even so: if I’m alone at night and there’s a crack in the curtains, and I rise from my chair to draw them, I don’t like looking at the dark beyond, for fear of what I’ll see.

As part of my army training, I did a two week course in Catterick Garrison, which is an army town in Yorkshire. I bedded down with the other trainees in Helles Barracks. We were quite a diverse bunch. There was a mechanic from Glasgow, whose name I forget; a mature student called Ben, who sat there reading The Art of War and droning on about Tai Chi; and a placid Welshman who never said much. When he did speak, he just seemed faintly bemused. Like he’d wandered in by mistake, and didn’t understand why people were shouting orders at him, or making him run around in fields.

Then there was Jim. Jim was older than the rest of us. I forget the maximum age for reserves, but I know he was very close to it. Despite his advanced years, he was clearly the fittest of the group. He had staring blue eyes, visible veins on his temples, and not a pound of fat on his body. He was obsessed with getting his resting heart rate as low as possible, and he had this off-putting habit of feeling his throat to check his pulse. I remember Ben saying that he wouldn’t be happy with his resting heart rate until he was clinically dead.

He came from a place that he called “Kersal”. At the time, I’d never heard of it. He made it sound like the Transylvania of the northwest. A spooky little corner of Greater Manchester, where gothic scenes played out in council flats, or on the banks of the River Irwell.

“I bet it was great in summer,” said Ben—meaning the river.

Jim smiled.

“Me mum wouldn’t let us anywhere near it,” he said. “We weren’t even allowed to go past the soapworks. She reckoned that river was haunted.”

“By what?”

“She called ’em ‘geggers’.”

“Ghosts?”

Jim shook his head.

“More like fairies. If one took a shine to you, it followed you home and gobbled you up in bed. Then it took your place. No one would know it wasn’t you.”

“Why did they do that?”

Jim felt his neck, counting the heartbeats.

“God knows,” he said. “Ask me mum.”

I shuddered in my bunk. Obviously, I didn’t believe in “geggers”—or rather, my brain didn’t believe in them—but it’s funny what you feel in your bones to be true, when it’s late at night and the goosebumps come. And the goosebumps were right, as I’ll soon explain.

I met my ex in Liverpool, at a pub called The Hole in the Wall. It’s tucked away in a long narrow street called Hackins Hey, and it’s meant to be the oldest pub in the city. It’s out of the way, but I’d heard it was there and made a special trip to see it, when I was on a job in St Helens.

The Hole in the Wall was built in the 1720s. I’m no expert but it seemed a lot older. Almost Tudor, in fact. The timbers were painted black. The first floor windows had cast iron lattices. It was grubby and charming at the same time.

Inside were dark wooden panels, gleaming brass fittings and a burning fire. There were room dividers with stained glass windows. Back then, you could still smoke in bars, so the air was thick with blue-grey fumes.

Louise was standing by the bar, rummaging in her handbag. She had gleaming red hair and matching lips. I was army-fit in those days and cocky with it, so I marched right up to the bar and paid for her drink, without even asking if she wanted me to.

“Thanks,” she said warily. “Who are you?”

“Paul. You?”

“Louise.”

I asked if she was from Manchester. She had that peculiar accent, like she was talking through her nostrils.

“Not quite,” she said with a smile. “Salford.”

“Anywhere near Old Trafford?”

She shook her head.

“North Salford,” she clarified. “Place called Kersal.”

I was surprised. I hadn’t quite realised that Kersal was part of Salford.

“I heard there’s a haunted river there,” I said. “Is that true?”

She gave me a withering look.

“It’s not true true, is it? Nowhere’s haunted. Not really. But we used to tell stories. There was a witch there called Wet Ethel.”

I laughed at at the image.

“Wet Ethel!” I said. “And what about—geggers?”

She looked at me blankly.

“Geggers?”

I shrugged and finished my lager. I was starting to wonder if Jim had been pulling our legs.

“Just something I heard about. It doesn’t matter.”

I offered to buy her another drink, but she insisted on getting the next round. It turned out she worked there and had only just finished her shift. We were still propping up the bar when her colleague rang last orders.

Two years later, she was pregnant and we were engaged.

We moved to Kersal to be close to her parents. I bought a house on Castlewood Road, just round the corner from the soap factory. It was the same one which, decades earlier, had marked the end of Jim’s permitted route, as decreed by his superstitious mum.

Beyond that was Agecroft Bridge, which carried cars across the Irwell.

Fate had led us to the haunted river.

When Sebastian was ten, I took him for a walk in Drinkwater Park.

We were following the river. The water’s meant to be filthy, but it’s a nice enough walk on a sunny day—and it was a sunny day. The air was almost swampy. A faint rotten smell kept wafting from the river. The sky looked raw, like a peeled blister.

I paused when I saw a giant drainpipe. It was sticking out from the far side of the river, spewing water from god-knows-where. It made a thunderous sound as it struck the surface, turning the river to white rapids.

“Look at that pipe!” I told Sebastian. “Look at all that water! Where do you think it comes from?”

He glanced across the river and his eyes widened.

“There’s someone in it,” he said in surprise.

“In the pipe?”

“Yeah.”

I turned to look again. All I could see was water coming out of it.

“Don’t be daft,” I said gently. “It’s empty. See?”

He was becoming visibly agitated, so I stopped trying to pique his interest. When we resumed our walk, he kept looking nervously around him. Then he slowed to a halt and just stood there, staring into the distance.

I started to lose patience.

“What?” I said brusquely.

He pointed down the river.

“There’s someone under that bridge,” he said fearfully.

“Where?”

“You just missed him. He’s hiding.”

I wasn’t convinced that Sebastian had seen anyone, but nor was I sure that he hadn’t. Older children often loitered in the area. Also, we weren’t far from Forest Bank Prison, which was right on the banks of the river. In the worst case scenario, it could have been a fugitive, trying to evade detection.

“What was he doing, when you saw him?”

“He wasn’t doing anything.”

“Ignore him, then. Come on.”

We walked past the bridge in silence. Once it was behind us, I risked a backwards glance over my shoulder. I couldn’t see anyone under it, but I’m not sure I would have done, from that angle.

The river shone like liquid fire, dazzling my eyes. And then—wait!—was that a dark figure—hunched over in the glare, like a goblin?

As soon as I saw it, it was gone. Was the light playing tricks on my eyes? I doubt I’ll ever know.

Some nights later, Sebastian woke me twice because of tapping on the bedroom window, which scared him.

It was a windy night and we had a tree in the garden. A large apple tree, which gave a yearly harvest of small inedible fruit. The branches must have been knocking the glass. The next day, I got a lopper from the shed and leaned right out of his bedroom window, cutting the branches down to size.

When bedtime came, I sent him to brush his teeth and promised to meet him upstairs, so I could check for monsters and tuck him in as always. Before I did, the phone rang. It was his mum, having some kind of drama with the bank. After a while of trying to help her untangle it, I promised to ring her back and got off the line.

When I went upstairs, the whole house was quiet. I wondered if he was already sleeping. I opened the door very slowly, just in case he was.

He wasn’t. His little white eyes shone in the dark. For some reason, his bedside lamp was off.

“Sorry,” I said softly. “That was your mum. You know what she’s like.”

When he didn’t respond, I went to his bedside and stroked his hair. It was fine and red, like his mother’s. I could feel heat and sweat coming off it, and wondered if he was coming down with something.

“I thought you might be sleeping,” I said. “No luck?”

He shook his head.

“Do you want me to check the wardrobe?”

He shook it again, which surprised me.

“No?”

He had the duvet pulled up to his nose. I looked at the wardrobe. In the dark, it was barely visible.

“What about the lamp?” I said. “Do you want me to turn it on?”

He didn’t answer, so I reached across the bed and pressed the button. With a sharp click, the wardrobe appeared in a pool of light.

The doors were ajar, which was strange. A vertical band of darkness ran between them, about as wide as my thumb is long.

In that narrow strip of gloom, I thought I saw a flicker of movement. One of the doors wobbled on its hinges.

A soft noise came from within, like a little gasp of air.

My mind raced but resisted horror. Surely, I thought—surely we’d let an animal into the house?

Then I remembered the bedroom window. I’d left it open when I’d finished lopping branches off the tree. Even now, the cheap curtains billowed by the bed, filling with air and slowly exhaling it. Synthetic fibres glowed in the lamplight.

It’s just an animal, I told myself. Probably a cat. That’s all.

“Stay there,” I told Sebastian.

I went to the wardrobe and opened the doors, bracing myself for a startled cat to shoot out of it.

It wasn’t a cat.

Hugging his knees on the sock drawers—cowering among his own school shirts—was Sebastian, my son.

He looked up at me in terror. My mind reeled as I heard his words:

“I don’t know who that is in my bed.”

As if in a dream, I turned to see.

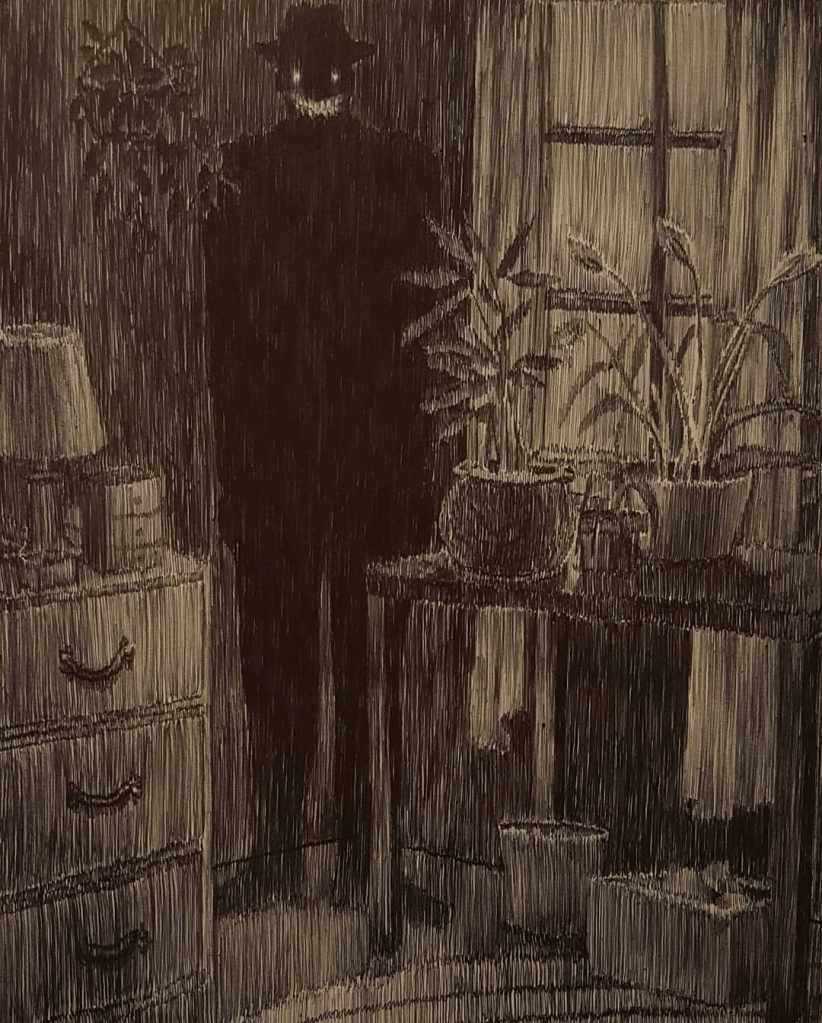

The thing in the bed that looked like my son was sitting up now—grinning right at me.

It wasn’t a perfect copy. The smile was too wide. Cheeks stuck out to make room for it. Five inches of grinning teeth, gleaming in the lamplight.

“Ge-e-e-egh!” it croaked—clacking its horrible jaws at me.

The room span, and I’m not ashamed to say I fainted.

Some time later I woke with a start.

It was dawn by then. The birds seemed aggressively loud. Through the wide-open window, liquid light came flooding in.

Sebastian was curled up behind me, still in the wardrobe. He was snoring softly with his hands on his face. I moved them gently to check his features. They were perfectly normal.

“Sebastian?”

He whimpered softly but didn’t wake. I picked him up and managed to carry him to my room. He woke briefly on the landing and stiffened with fear, so I held him tight and shushed him.

“You had a nightmare,” I lied.

When we rose at noon, he showed no signs of remembering—but nor did he ask why he’d slept in my bed—so I guessed that he remembered something. Maybe just being carried. A vague recollection of a night terror.

I knew that I’d come face-to-face with a “gegger” that night, so Jim’s words came back to haunt me: “If one took a shine to you, it followed you home and gobbled you up in bed. Then it took your place...”

I kept glancing at Sebastian, looking for clues that something was amiss. Was it my real son? Or a changeling? In the days that followed, I asked him questions, checking for things that no one else would’ve known. I came to the conclusion that, if it wasn’t him, it was doing a damn good impression.

But that left a lingering mystery: why didn’t the gegger take him when it had chance?

The terrible thing is, I’ll never know what happened when I was out cold. All I can say for sure is, when I fainted, I collapsed right in front of my son. Maybe that was enough to discourage the gegger? It would have needed to climb over me to get at Sebastian. Was that enough of a deterrent?

I guess so. And yet…

Here’s what bothers me, even now. After the events of that terrible night, my son no longer needed me to tuck him in, or check inside the wardrobe for monsters. In that regard at least, he was a changed boy.

I like to think that, somewhere in his brain, his subconscious knows what happened that night, and the experience toughened him up. It’s a nice idea, because the alternative is unthinkable.

I have a recurring dream, or rather nightmare, and hope to God it won’t come true. I dream that I’m an old man, lying at last on my deathbed. Sebastian sits beside me. I can hear the peep—peep—peep of my heartbeat slowing down on the monitor.

When the time comes for me to die, he takes my hand and leans across the bed. I look up at his face. When I do, he smiles a terrible smile that’s far too big, and I know the monster got him after all.

Ellis Reed, 08/03/2024

(Author’s note: this story took some inspiration from a two sentence horror story by Juan J Ruiz.)