This is another manuscript from the personal collection of Keith Credge (1943-2004), who was known in and around North Manchester as a psychic and spirit medium.

In the last years of his life, Mr Credge believed that the spirits of the dead were telling him their stories, which he recorded for posterity. The following text is very reminiscent of those narratives, apart from the fact that it was titled like a piece of creative writing (“The Hungry Waves by K. R. C.”) and written entirely in the third person. By way of comparison, most of the confirmed spirit-writings start in the third person and then drift into first (perhaps suggestive of a deepening trance?) and are simply signed/dated at the bottom.

For these reasons, the Society is split on whether this is a) another example of Credge’s spirit-writing or b) his only known attempt to write a piece of fiction. In either case, the handwriting is unmistakably his, so we encourage you to read the transcript below and reach your own conclusions.

Broughton Society for Paranormal Research, 22 February 2024

The wind was a cruel master that night. It circled the dark shore, whipping the waves into white froth.

From the comfort of his hotel room, John could only listen in horror. The sound of the sea—how did anyone find it soothing? It was all he could do not to scream.

He teetered on the edge of sleep for a very long time, tormented by the noise of crashing waves. Before he nodded off, he had the perverse idea that the beach and his brain were the same thing, somehow—because the night’s terrible logic had made them one—and the waves that beat the rocks were violently smashing his own cerebral cortex.

Then he had the idea that his brain had gone down to the bottom of the sea, to get away from the violence of the storm. A strange feeling of calm washed over him. Suddenly, he was content to lie there forever. Like a piece of coral, nibbled by the crabs, somewhere at the bottom of the Norwegian Trench.

For a few fleeting moments, he was asleep. Then the waves surged and startled him awake.

He groaned and opened his eyes. Where was he?

He didn’t have to wonder for long. Soon, he began to discern the faint shapes of the hotel bedroom. The no-smoking sign on the door; the electric kettle on the small round table; his own raincoat draped across a chair, like a drowned sailor sprawled across the rocks.

I need to get out of here, he thought desperately.

Ten minutes later, he’d left the hotel and was staggering through the moonlit streets. He wasn’t going anywhere in particular; just trying to get away from the beach, so he didn’t have to listen to the awful waves. He cursed them, and he cursed his own self for being there.

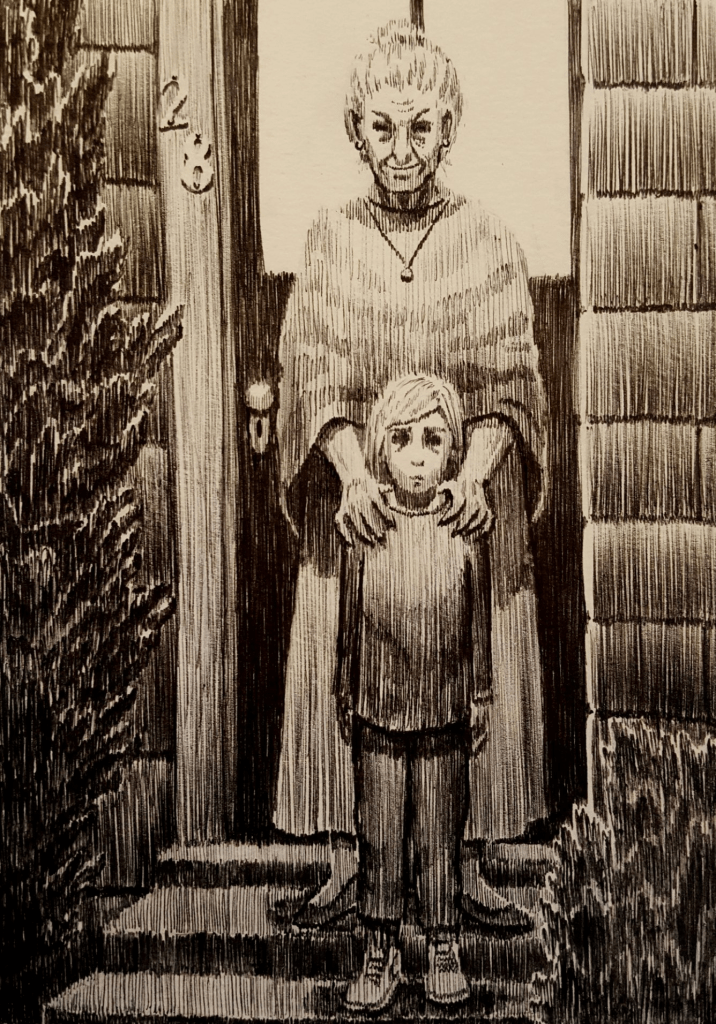

He had a fear of the sea—a crippling, irrational fear that he could only call a “phobia”—and the point of the trip had been to face that fear and hopefully overcome it. With this in mind, he’d organised a tour of the east coast of Scotland, where the sight of it would be unavoidable.

And it really had been unavoidable! Sometimes, it even seemed to jump out at him, springing into view the second he turned a corner, or leering through the gaps between buildings.

The other tourists couldn’t get enough of it. “Would you look at that sea!” they would say. “Isn’t it beautiful?” And he would agree that it was, because it was easier to lie.

But it wasn’t beautiful. Not to him. In his harrowed mind, it was a slobbering monster. A creature so hungry it was nothing but saliva, endlessly drooling over Seafield Beach, or Kinghorn Beach, or the grim grey cliffs that stood beneath the ruins of Tantallon Castle.

He tried to banish it from his thoughts. He would face his fears tomorrow. For now, he wanted to get as far away from them as possible.

On he went, zigzagging further inland. As he marched up the moonlit street, he hugged himself in his coat—or what he thought was his coat—and realised, with a bitter laugh, that he’d accidentally put his dressing gown over his shirt. It was a measure of how disordered his thoughts were. How hard it was to think, when the hungry waves were eating the ground from under him.

He hadn’t always been scared of the sea, of course. It had all started in his penultimate year of primary school, when someone had lent him a picture book about the RMS Titanic.

The Titanic! The thought of the disaster still made his stomach turn. Fifty-two thousand tons of luxury ocean liner, swallowed by the North Atlantic Ocean without so much as a burp.

Reading about the Titanic had been a watershed moment in his life. It was the first time he’d asked himself the one terrible question, which had since become his monomania: what was it like to drown?

The next summer, when they’d gone to Great Yarmouth, he’d sat on the beach in his swimming trunks, refusing to go in the water. Again and again, his thoughts had returned to that one terrible question, like a doomed swimmer circling a whirlpool: what was it like to drown?

The book itself was long gone, but he recalled parts of it with feverish intensity. The worst passage, by far, was the bit about the ship’s funnels.

Oh, God—the funnels.

Even now, the thought of them made his skin crawl. When the ship had gone under, four giant funnels had filled with water. Dozens of swimmers had been sucked into them, never to be seen again. That had been the fate of so many passengers: to be gobbled down by the greedy ship, just as they were trying to swim away from it.

And God only knew what that was like. To be trapped in a sinking ship, chest bursting, heart pounding, head spinning, till you had no choice but to open your mouth and inhale the ice-cold sea…

The thought was more than John could bear. He stopped walking and threw up on the pavement. Then he wiped his mouth and staggered away, a brief sob escaping his lips, the sound of the sea still ringing in his ears.

Eventually, an old couplet surfaced in his mind.

Come unto these yellow sands, / And then take hands…

He stopped in his tracks, briefly beguiled by the sing-song invitation. It came, of course, from Shakespeare’s The Tempest. They’d all had to do it for their GCSEs, and, one fateful afternoon, John had been picked to read Ariel’s lines to the whole class. He remembered perching on the corner of his desk, revealing (or rather pretending) that Alonso had drowned in a shipwreck.

“Full fathom five thy father lies,” he’d told his classmates. “Of his bones are coral made…”

Then something strange had happened. As he’d uttered those famous words, his head had started to spin. The face of a drowned sailor had flashed across his mind.

“Those are pearls that were his eyes,” he’d managed to squeeze out. “Nothing of him that doth fade, but doth suffer—uh—”

His voice had started to wobble. His hands had started to shake. Before he’d got to the end of his lines, he’d suffered a full-blown panic attack, making him flee the classroom in terror.

His peers had responded with two whole seconds of stunned silence, followed by the inevitable howls of laughter. Loud, shrieking, mean-spirited laughter. The sound of it had chased him down the hall, through the fire exit, all the way across the playground. It still haunted him, even now—thirty-one years and two hundred miles away.

Back in the present, it had started to rain. Even at this ungodly hour, John could hear the brrrr, brrrr, brrrr of a mechanical billboard switching ads. The night stank of dead fish and iodine.

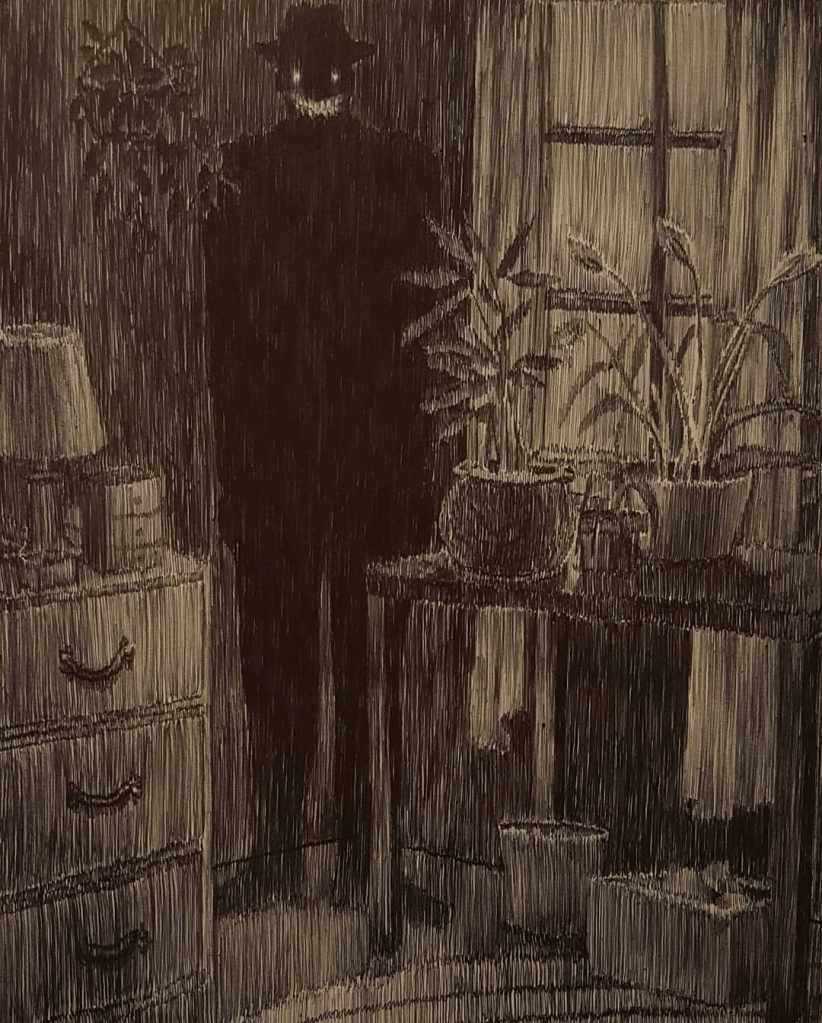

More than once in Scotland, John had wondered if his phobia was actually getting worse. He’d also started to wonder if the distinction between neurosis and psychosis was as clear-cut as he hoped it was.

For instance: just a few days ago, he’d gone to Musselburgh for ice-cream. It had seemed like a natural thing for a tourist to do, and he’d been determined to do it.

Suffice to say, it hadn’t gone well.

He remembered standing on the beach, slowly eating two small scoops of rum and raisin. The sun had seemed doomed and desperate that evening, throwing up orange distress flares as it sank from view.

During those haunted moments, the terrible sea had spread itself before him—uncanny in its perfect flatness—seeming to sparkle with pure malevolence. He’d felt like it was taunting him, somehow.

And then he’d seen them.

Those old schoolmates, trapped like flies in the orange light. They weren’t laughing any more. They were up to their necks in water, repeatedly going under, grasping at the air in desperation.

He hadn’t panicked or called for help because he’d known at once that the vision wasn’t real. Instead, he’d watched their doomed struggle in silence, till they’d slid beneath the waves like a team of synchronised swimmers, never to be seen again.

And that wasn’t all.

Later that day, during a downpour, he’d actually heard the sea laughing. Deep, malicious laughter, booming out across the North Sea, shocking the seagulls from the wooden pier.

The next morning, the sound of waves had been too much to bear, so he’d got in his car and headed for the Cairngorms National Park, desperate for a bit of respite. Halfway there, he’d realised with horror that he could still hear the ocean, even though he was twenty miles inland. How was that even possible?

He remembered desperately fiddling with the car stereo, thinking it was somehow coming through the speakers, but it wasn’t. It was all in his head. So he’d given up and returned to the coast, and that was then and this was now.

Full fathom five thy father lies…

He stopped dead on the street and stifled a gasp. For a moment, he’d almost forgotten that his own father had drowned.

He’d been just seventeen at the time. His parents were already separated by then. He hadn’t seen his father for nearly a year.

Of his bones are coral made…

Apparently, the old man had gone for a swim near Camber Sands. Later that morning, they’d fished him out of the Channel, as dead as a doornail.

Those are pearls that were his eyes…

In John’s mind, his father had suffered a sea-change that day. Ghostly wet hands had pulled him to the ocean floor, reforging his body in the strange flooded foundry of Hurd’s Deep. By the time they’d got him out of the water, his ribs had turned to living coral. His eyes had turned to blind white pearls. That was how it was in John’s mind; his father had been turned from a living man into something “rich and strange,” as the Bard had put it.

John cursed the universe for its dark sense of humour. How unlucky it was for someone like him, who already had a pathological fear of the sea, to lose his own father to the hungry waves.

And to make matters worse, his phobia was so bad that he hadn’t been able to grieve. Not properly. Any feelings of sadness or loss had been washed away by the one terrible question, which kept returning like the tide: what was it like to drown?

For John, it wasn’t just a mystery. It was the only mystery. As a child, a teenager, a young adult, a middle-aged man—again and again, that same terrible question: what was it like to drown?

Eventually, his thoughts returned to the present. He was standing on the seafront, he realised—but why? He’d been heading away from the sea. Not towards it.

Victorian streetlamps lit the promenade. The arcades were shuttered. The shutters were covered in graffiti. The chip shop windows were inscrutable black mirrors, reflecting nothing at all.

The sea itself was invisible, but he could still hear it. Oh, god—he could hear it! An indescribable wall of seething white noise, which had haunted his dreams for thirty-one years.

It was the sound of the waves. The hungry waves, devouring and digesting themselves and each other, puking themselves up the beach, higher and higher, again and again till the end of time.

Full fathom five thy father lies…

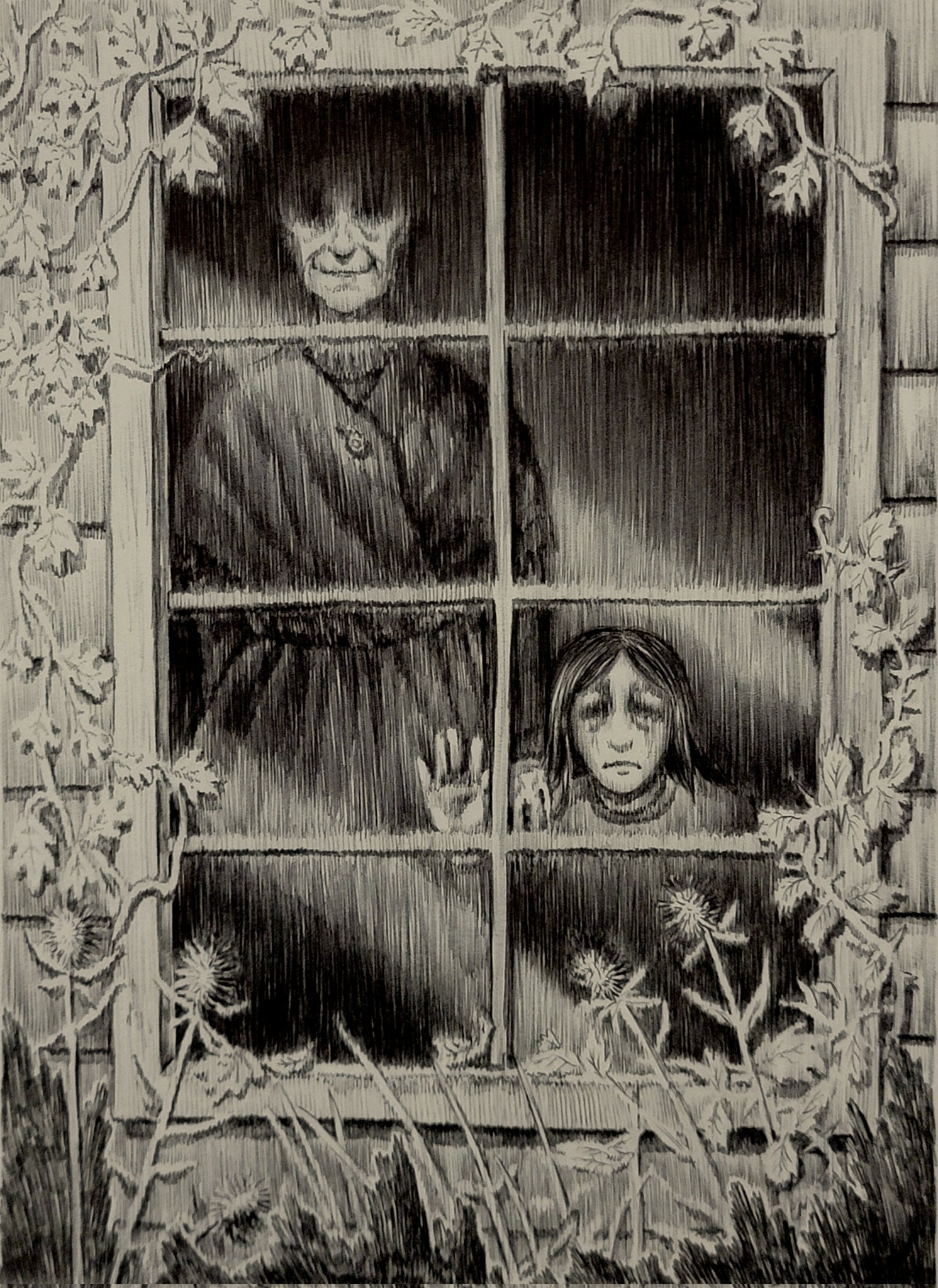

Somewhere out there was his father, he realised. A grinning corpse with pearls for eyes, and live coral bursting from his bones. They’d buried him in the ground but he wouldn’t have stayed there. Oh, no! He would have wriggled up from his grave like a marine worm and slithered all the way to the nearest shore, vanishing into the waves with a soft wet plop. He belonged to the sea and would return to it always.

John laughed bitterly. He belonged to the sea as well. Ever since he’d read that bloody book…

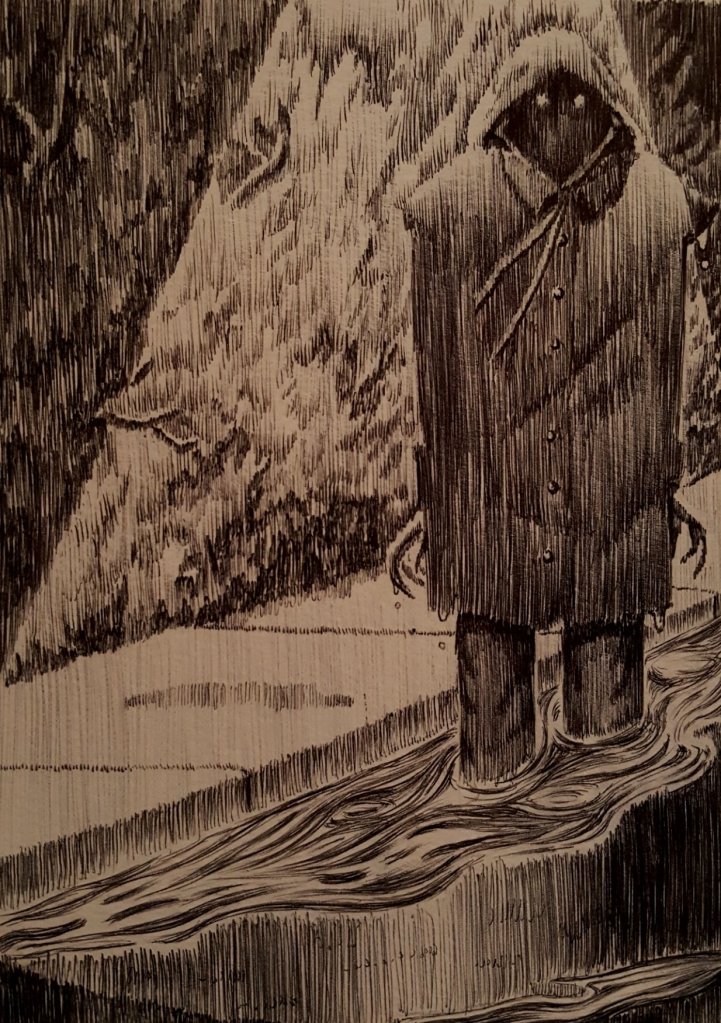

As if in a dream, he walked down the old stone steps and across the sand, seeming to float over it. The gulls became a Greek chorus, willing him to his doom. He wasn’t controlling his legs any more; they just carried him along like an ocean current.

What was it like to drown?

Suddenly, his feet were in the sea. It was right there, lapping at his legs: the ever-moving tide, racing up the shore to meet him halfway.

What was it like to drown?

His shoes filled with water, but he didn’t care. He just kept going. Before long, it had reached his knees—his waist—his neck.

What was it like to drown?

He could hear so many things now. The crying of the gulls—the hissing of the waves—the too-cruel laughter of the other children. A faraway voice in his own head that was suddenly screaming You’ve lost your mind John, your dad didn’t drown, he got in trouble off the coast but he didn’t drown, he’s at a care-home in Bolton for God’s sake, but it hardly mattered. Not now. All around him, sea-nymphs rang his knell. Hark—he could hear them!

What was it like to drown?

He had to know.

With that one simple thought, a terrible weight had lifted from his shoulders.

It was that straightforward. He had to know.

He gritted his teeth against the cold and began to swim, shaking his shoes off, pulling his weight through the water. He’d spent his whole life wondering, and now he had to know.

Whatever the cost—whatever the consequence—he simply had to know.

Ellis Reed, 26/03/2024