I don’t know where Grandma came from, but it must’ve been somewhere, and wherever it was, it surely wasn’t here.

She had the faintest trace of an accent, which seemed to recall the gloomy pines of the Black Forest, or maybe the foothills of the Carpathians. Her mottled arms were always brown, like she’d caught the sun in a faraway land and never let it go.

She knew the ways of the woods and wild places, but if you asked where they were, she’d only smile and shrug. Not in the innocent way that meant she didn’t know, but the impish way that meant she wouldn’t tell you.

Her teeth were long and yellow, and I once saw her pluck a spider from its web and eat it whole when she thought I wasn’t looking. It was the only thing I ever saw her eat that wasn’t a beef paste sandwich or tinned fruit. She drank steaming brews that she called “tea”, but they didn’t smell like normal tea. I felt then, and feel now, that she was a witch.

We saw a lot of her because she lived at the far end of our street, which was a place called Nevile Road. From an early age, my sister and I were allowed to walk between the two homes, past the football ground and little school, and the tiny power station (or whatever it was) with the sign that said it would electrocute you. From Monday to Thursday, Mum would still be working when school finished, so we had to wait at Grandma’s for a phonecall.

From the outside, Grandma’s house was no different to the neighbours. It had PVC windows and render on the first floor. Inside, it smelled of incense and raw meat, and something else you couldn’t name. On the smoke-stained walls were pictures of strange gods, like the masked woman with the moon on her head, or the one with horns who sat like Buddha. When I asked Grandma who they were, she just smiled and shrugged.

She had a lot more patience with my sister. Maybe because she wasn’t a boy.

“Do you believe that people have souls?” my sister asked her, when she was making a beef paste sandwich.

“I do,” she replied—slopping it on the bread. It smelled like dog food and sparkled wetly.

“Where do they go when we die?”

“Nowhere,” said Grandma. “If your soul is in your body when it dies, it simply dies as well.”

I looked up from my comic.

“What’s the point of a soul,” I wondered, “if it dies when you do?”

She just smiled and shrugged and ate her sandwich.

I’d say that Grandma took a special interest in Sarah, which was fine by me, because their conversations sounded like hard work. Once, when I went upstairs to use the toilet, I heard them talking in one of the rooms. It had been a bedroom once and now was full of knick-knacks.

“Liberate your mind,” Grandma was saying. “Separate the spirit from the flesh.”

“I don’t know what you mean,” my sister groaned.

“Of course you do,” Grandma snapped. “But you’re breathing wrong. Use your mind instead of your lungs. Breathe the light and not the air.”

It looks very mysterious when I put it down on paper, but at the time, it just sounded boring. Grandma had the weary tone of a Latin master, ordering a child to conjugate a verb for the hundred thousandth time. I’d heard stuff like this before, but gave up asking what it meant, because my sister got embarrassed, and Grandma just smiled and shrugged. Better Sarah than me, I thought. I continued to the toilet, then back downstairs to read my comic.

Grandma’s death, when it came, was surprising but swift. I believe she got a rare kind of dementia that happened overnight, which must’ve been vascular, or maybe the result of a stroke (if that’s not the same thing). We never saw her like that because Mum thought it would upset us. “It’s like she’s a child again,” she said tactfully. When I begged for the detail, she added: “Well basically, she’s forgotten who she is. She thinks I’m her mum, and she’s always scared, and it’s not nice to see.” When she took over Grandma’s affairs, it turned out she’d been living with terminal cancer, which was almost a mercy, given the state of her mind.

We never saw her again. I believe she was looked after in a special kind of hospice till she died two months later, the day before Christmas Eve.

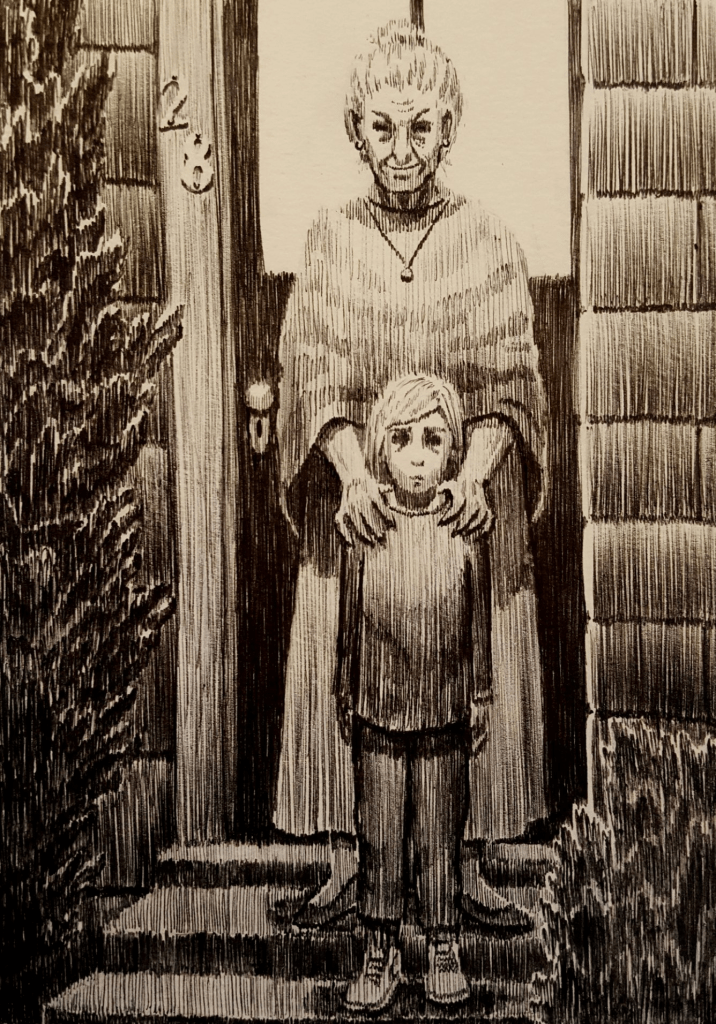

The last time I saw her was the day before she lost her marbles and got taken away. It was a crisp October evening, midnight-dark at eight p.m. The autumn air was like cold hands pressing my face. We’d been waiting with Grandma after school as always, and Mum had just phoned, so we were leaving the house to walk back home.

“Sarah?”

It was Grandma’s voice. We turned to see her standing in the door. The hall behind her was a strange haze of orange light and incense smoke.

“I’m ready,” she said. “It has to be now.”

I looked at my sister in confusion.

“What does she mean?”

“I don’t know,” Sarah admitted. “It’s like—a weird prayer I had to learn.”

“What kind of prayer?”

“Oh, some stupid thing. You know what she’s like. It won’t take long.”

She went to join Grandma inside. I took a couple of steps to follow, but before I could, a long brown arm snaked out of the light, slamming the door in my face. I waited by the gate with with my school bag, hoping it wouldn’t take long.

I don’t know how much time went by, but I know I heard a faint cry inside. Suddenly, the wind seemed to quicken around me, and the dark was somehow darker. I was gripped by an irrational fear, like cold water filling me up. It reminded me of the moment in a bad dream, when you know, without knowing how, that something awful is going to happen.

The feeling vanished. The door opened and my sister came out, walking with a strange new posture.

“What happened?”

“Nothing,” she said. “Come on.”

I looked at the house and saw, to my surprise, that Grandma had come to one of the windows. She pressed her hands to the glass and looked out in fright, like she couldn’t believe what had happened.

“Is she okay?”

“She’s fine.”

I hurried to follow my sister down the road.

“What did you do in there?”

She just smiled and shrugged.

Grandma’s house was left to Mum, who left it in turn to Sarah and me.

By then, we were all grown up. Sarah bought my half and kept the house to live in. She remains at the end of Nevile Road, and survives, as far as I can tell, on beef paste sandwiches and tinned fruit. She knows the ways of the woods and wild places.

I sometimes remember what Mum said about Grandma’s “dementia”, but I try not to, because the implications are too awful to contemplate.

“She thinks I’m her mum, and she’s always scared…”

Sarah and I aren’t close nowadays, but I see her from time to time. When I point out the uncanny resemblance between her and Grandma, it always makes her chuckle. People even say she has Grandma’s laugh, which is strange, because it’s true. And I swear she never used to.

Ellis Reed, 02/09/2020

I really liked this. You time the reveal perfectly so that it dawns on the reader exactly what’s happening JUST ahead of the narrative reveal. A masterful bit of pacing.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Horrifying and great! Grandma is a bit creepy, but not malicious, but once your realise the reveal and all the foreshadowing leading up to it! Shivers! What an awful fate!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much! 😃

LikeLike

Wow wow. For extra effect.

LikeLiked by 1 person